Regulation

Coronavirus:

the impact on global shipping

The rapid spread of coronavirus in early 2020 has had a major impact on global shipping markets, with the slump in demand for goods from China having a ripple effect on everything from container ships to oil tankers. Adele Berti takes a look at how events have unfolded so far, and asks how the industry could speed up recovery in the future.

Initially, everyone

thought that it was China’s problem. Nobody thinks that anymore. The first country to be hit by Covid-19 is now the only one with a recovering economy and re-emerging population. For the rest of the world, uncertainty is the only certainty.

The soon-to-be global pandemic began in late December with only a dozen cases in Wuhan, China. The coronavirus outbreak has now tightened its grip on the entire world, with Europe as its current epicentre. As of 27 April it has now infected more than three million people and claimed more than 200,000 lives.

With Western countries now enforcing nationwide lockdowns that could last for months if not years, world economies are in danger of bleeding out. Numerous industries are at a standstill and the shipping sector is navigating uncharted waters.

Over the past two months, Ship Technology Global has been speaking to analysts and experts - both directly and indirectly - to offer a comprehensive view of how the global pandemic is affecting the industry.

January: a shock for the Chinese maritime sector

Prosperity within the shipping sector has long been strongly tied to China, a major trade partner for several countries and a key leader in shipbuilding.

Throughout January, during which the virus started spreading across the rest of the country and to its neighbours, the industry seemed to experience only a marginal impact - initially witnessing only a minor fall in demand as ports in China and nearby countries started operating at limited capacity.

“The outbreak came at a time when shipping companies are used to lower demand due to the Chinese New Year (CNY) and had already planned for this, for example by blanking sailings in the container shipping industry,” BIMCO chief shipping analyst Peter Sand told Ship Technology Global magazine in March.

The situation largely deteriorated as January passed by and the CNY holidays were extended. After a passenger tested positive for Covid-19 onboard a Princess Cruises ship off the coast of Japan, ports started limiting - and eventually banning - cruise traffic at their terminals. Asian ports in countries including South Korea, Taiwan and Singapore also started introducing screening procedures at their hubs, putting Chinese crews under quarantine and working to limit the spread of the virus.

Coronavirus caused demand to fall lower, and remain at lower levels for much longer than in a usual year

From the very beginning, these initiatives caused significant setbacks for both the cruise and shipping sectors, which found themselves dealing with orders and trips cancellations, spikes in costs and a drop in trade opportunities. In addition, Chinese shipping was hit by a nationwide ban on all non-essential travel, a largely reduced workforce and the closure of production and shipbuilding facilities.

As BIMCO’s Peter Sand puts it: “Coronavirus caused demand to fall lower, and remain at lower levels for much longer than in a usual year; for many in the industry it became about prolonging their measures for dealing with CNY, which were already in place, with little other options to deal with the blow.”

According to figures from Chinese think-tank the Shanghai International Shipping Institute, this led to reduced capacity utilisation - which fell between 20% and 50% at the biggest Chinese ports - and a sharp increase in the use of port storage facilities.

Major ports across the world adopted a 14-day quarantine period for vessels arriving from or transiting through China.

February: the impact on global shipping

Despite Asia’s prolonged struggles, it wasn’t until February that the global shipping sector started to really feel the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic.

As IHS Markit principal consultant Daejin Lee explains, shutdowns and limited activity further led to labour shortages across Chinese maritime segments, which in turn affected trade.

“Exports from mainland China have dropped significantly in February 2020 as the Purchasing Managers Index compiled by IHS Markit dropped from 51.1 in January to 40.3 in February,” he says. “It is not surprising but still massive; it’s the sharpest deterioration since our survey started almost 16 years ago.”

Mid-February data from market intelligence service VesselsValue showed a radical drop in demand for Chinese crude tankers from an average of 3.4 billion tonne miles per day in 2019 to almost zero. According to the company’s Charter Rate assessment, the daily cost of hiring a very large crude carrier (VLCC) for a year plummeted by over 20% between 14 January and 14 February 2020. Spot earnings also decreased by more than 70%.

This was just the start of what was about to become a global crisis for all sectors including shipping, which was hit by slowing demand in goods’ production, exports and oil. Here are some of the key figures from February.

VesselsValue chief operating officer Adrian Economakis told us in early March: “In terms of rate, the most significant affected have been the large crude tankers and the large bulkers. China is a significant importer of crude oil, usually through VLCCs, so the reduction in economic activity in China is certainly having a negative demand effect for crude tankers.”

The reason that coronavirus is having particularly horrendous effects on the shipping industry is its relationship with China

Analysis from BIMCO is further testament to this trend, as it showed VLCCs and overall tanker freight rates were subjected to heavy downward pressure towards the second half of February. “Earnings from the Persian Gulf to China have dropped from $103,052 per day on 2 January to $18,326 per day on 18 February 2020,” said a blog post from BIMCO at the end of the month.

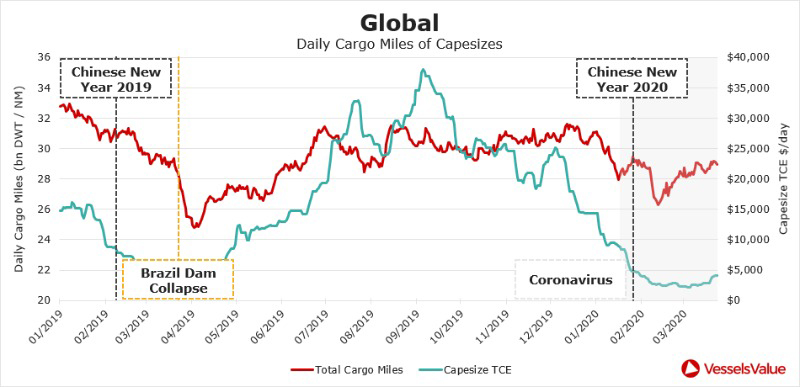

In February, capesize was another heavily affected category, which is in largely driven by China. “The problem with capesize is that the market had been terrible anyway, and it’s gotten even worse,” saidEconomakis in March. “It is effectively reaching a five-year low at around just over $2,000 a day earnings, which means they're losing a lot of money per day.”

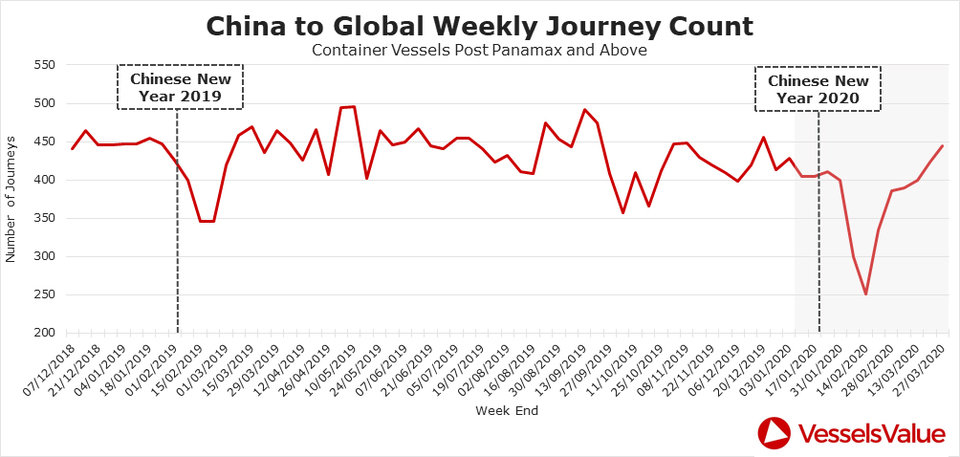

Finally, the container sector, another category that significantly relies on China, fell victim to the coronavirus outbreak. As Economakis put it, “The container sector is naturally less liquid but we have seen a reduction in rates and values. Containers are the most closely linked to economic activities and economic activity is down all around the world.

“The story here is the reason that coronavirus is having particularly horrendous effects on the shipping industry is its relationship with China. China really is the driver of the shipping industry. We are so dependent on Chinese demand and also Chinese exports, so demand for raw material, exports of a finished product for driving cargo volumes and cargo demands.”

Image: VesselsValue

The Port of Shanghai, China.

March: coronavirus in Europe

The coronavirus crisis escalated to unprecedented levels in March. Even though deaths in China slowly started to decrease, an ever-growing number of cases started appearing in Europe. Soon after the World Health Organisation declared the Covid-19 outbreak a pandemic, the whole of Italy was put into lockdown and was quickly followed by Spain, France and, towards the end of the month, the UK and some US states.

“The virus is still spreading like wildfire,” says Navin Kumar, director of Maritime Research at Drewry. “The impact is already visible. Trade has been severely impacted, charter rates are down, supply chains have been disrupted. The world has been too dependent on China for everything. And this pandemic has come as a rude shock to them.”

During a webinar hosted by BIMCO and Bloomberg Intelligence in March, BIMCO’s Peter Sand introduced his presentation with a gloomy forecast: the International Monetary Fund expects the global economic outlook in 2020 to reach at least the same levels as the Global Financial Crisis - meaning a world recession is inevitable.

Needless to say, this means that future months could become increasingly harsh for the whole global sector, which will be forced to operate in a limited way. This, Sand stressed, is not going to be the sole result of the coronavirus pandemic but rather a ripple effect of its spread, the introduction of the 2020 sulphur cap by the International Maritime Organization, and the failed implementation of the US-China phase one trade agreement.

“After a disastrous 2019, the shipping industry would have definitely benefited from the trade deal between US and China,” confirms Drewry’s Kumar. “The trade deal required China to import a certain volume of some commodities in 2020.”

Container shipping [could soon be] developing into the epicentre of the crisis in the global shipping industry

Narrowing down on sailings, BIMCO analysis showed all sub-categories of shipping will soon fall prey to the situation. In the dry bulkers’ realm, for example, freight rates have suffered as a result of IMO 2020 and coronavirus, though the capesize sector has also witnessed even harder times.

Meanwhile, demand for oil tankers is currently on the rise as the breakdown of the OPEC+ alliance - which triggered a 30% fall in oil prices and a potential price war amongst world leaders - is supporting Arabian crude oil exports. Nevertheless, Covid-19 is expected to heavily damage oil demand for 2020, something that will negatively affect oil freight rates in the coming months.

Finally, said Sand, “container shipping [could soon be] developing into the epicentre of the crisis in the global shipping industry, due to the fact that containerised goods, being produced in East Asia predominantly have already been hit".

Demand in this realm continued to slow, partially due to the postponement of the CNY, the missed introduction of the China-US agreement and struggling economies in the west.

“Production facilities in China may have workers now, but in terms of productivity we are still not seeing 100% of activity,” said Sand. “The number we saw from late last week was an indication of around 70% of productivity. And then of course, in order to see a sustained flow of cargo out of the Far East, we can only see the backlog of orders to be delivered right now. And right now we're fairly busy doing something else in the Western world to keep orders coming.”

Image: VesselsValue

Image: VesselsValue

April: signs of recovery?

As the world enters the fourth month of the coronavirus pandemic, the data from VesselsValuelooks more encouraging. In particular, Economakis said in April, "capesize cargo mile demand has recently improved in late March, led by a recovery in demand from Japan and South Korea, although Chinese figures are still low". With rates just under $6,000 earnings per day on 1 April - up from $2,000 in early March - he says improvements should be expected in the future.

A recovery also could in the cards for the container sector, with the weekly number of large containership journeys originating in China now going back up. "Now many sectors are showing recent recoveries in demand, which should lead to improvements in the markets," adds Economakis. "However, the situation developing daily is so critical to keep a careful and regular eye on the evolving demand data.”

During his webinar, Sand also pointed to the demolition market as a silver lining. “We are continuously operating in a market with too much capacity but as for dry bulk shipping, we have seen five million deadweights being sold for demolition in the first (almost) three months of 2020,” he said during the webinar.

One way to limit peak growth is to demolish overaged or at least commercially lesser superior tonnage

"One way to limit peak growth is to demolish overaged or at least commercially lesser superior tonnage.”

Although undoubtedly positive news, this trend is already slowing down as the pandemic takes over India and its neighbours Bangladesh and Pakistan, which own some of the largest demolition yards in the world.

“However, we are going to see much lower demand growth,” Sand added. “We need to offset this negative effect by also limiting peak growth. And one way to limit peak growth is to demolish overaged or at least commercially lesser superior tonnage by taking it away from the market.”

In addition, the current delay in deliveries from China is providing some much-needed relief for an oversupplied market like shipping.

Finally, adds IHS Markit’s Lee, additional relief could come from “enforced delays in shipbuilding and repairing activities including scrubber installation", and "delayed but not cancelled trade deals may support shipping demand in the medium term”.

India, Bangladesh and Pakistan are home to some of the largest demolition yards in the world.

The need to keep globalisation alive

Ever since Europe became the epicentre of the Covid-19 spread, a sentiment widely shared across all Western markets and beyond is that there is a firm need to keep the economy going, something that is not only paramount to individual countries but also the globalisation-dependent shipping sector.

“One of the biggest long-term impacts of this outbreak will be that now countries/companies will be wary of putting all their eggs in one basket,” explains Kunar. “People will surely look into diversifying their supply chains.”

We need to make sure that local ports and terminals are kept open for business

Echoing Kunar’s words, Sand highlighted the urgency of leaving ports open in the most continued manner possible. “It's extremely important to keep the flow of goods running and the reply to this crisis is not to go back on globalisation,” he commented during his webinar. “That will not be good for shipping, that will not be good for consumers, that will not be good for governments anywhere.

“We need to make sure that local ports and terminals are kept open for business. By saying that we recognise that naturally there is a global need for containing the spread, and we need to deal with it in a sensible manner in order to make sure that food and goods are kept flowing to where it's needed because that's basically where shipping lands a lifeline to the global public.”

Unlocking new investment in freight technologies

While it’s almost impossible to make short-term forecasts for the shipping sector once the pandemic has slowed, Paul Cuatrecasas, CEO of investment banking firm Aquaa Partners and author of Go Tech or Go Extinct, believes the post-coronavirus years will be all about digital disruption.

In a media briefing held at the end of March, Cuatrecasas explained how the health crisis might spur investment in different segments of robotics and freight technology, which will in turn lead to a change in headwinds across the sector.

“Demand has dropped across the board, including at ports, the trucking industry, the shipping industry, almost anywhere you look,” he said. “Covid-19 has just slapped everybody in the face so get ready because what's coming is going to be even greater disruption in different forms.”

But disruptive doesn’t necessarily mean damaging, as he mentioned the crisis could become a key catalyst for digital and technological advancements in the shipping industry.

Covid-19 has just slapped everybody in the face, so get ready because what's coming is going to be even greater disruption

Change in these regards could be threefold. The first step will be increasing investment in freight technologies as well as companies providing data analysis, artificial intelligence software and overall end-to-end supply chain management. This will be key as it “reduces the shock, increases the resilience, [providing] more data, more information, greater ability to manage inventories to track the rates and timing of the shipping that is done”.

Increased investment in these segments will be accompanied by growth in the autonomous transportation sector, paving the way for autonomous shipping. “This is not just because [automation] is cheaper, or more efficient,” he said. “The nature of autonomous activities is one that can solve many, many problems, and deal with resilience in the core.” Lastly, there will be more space for cultured meat and fish, something that will disrupt the entire supply chain.

These will translate into the further evolution of e-commerce into a largely tech-savvy industry with cargo drones, 3D printers and robotics at its disposal. “Covid-19 will have a disruptive power across all industries but particularly in the supply chain and in the transportation sector, it won’t just be in the short term,” he concluded. “Investment into freight tech companies will help the existing industry to connect all the different players, shippers, brokers and carriers in the maritime basis to optimise current operations.”

The crisis could spur investment in new technologies, paving the way towards autonomous cargo ships.

Timeline:

Coronavirus sweeps the global shipping and cruise industries

Jan

2020

The first dozen cases of coronavirus were recorded in Wuhan, China, in December 2019. Having registered 25 deaths and over 600 infections in less than a month, in late January the Chinese Government decided to ban ships from entering the Port of Wuhan. On the same day, Singapore started temperature screening procedures at all its port’s checkpoints and several cruise liners cancelled trips to China.

Feb

2020

American cruise liner Princess Cruises’ Diamond Princess entered the first day of a long quarantine off the coast of Japan after one of its passengers tested positive for coronavirus. The ship soon became the place with the highest concentration of cases outside of China. Non-affected passengers were not allowed to leave the ship until 19 February - leaving 621 who tested positive on-board.

The fast spread of the virus beyond Chinese borders accelerated preventive measures among its neighbouring port cities and countries. A key step in this direction was Hong Kong’s decision to close its cruise terminals and put all in-bound Chinese travellers into quarantine. Taiwan soon adopted similar initiatives.

Analysis from SeaIntelligence showed container lines were suffering losses of between $300m and $350m per week as a result of decreased traffic. In the space of a week, the study found some 31 new sailings were blanked in the transpacific and Asia-Europe trades in the space of a week.

The International Maritime Organization (IMO) and World Health Organization (WHO) published a joint statement in a bid to ensure “that health measures are implemented in ways that minimise unnecessary interference with international traffic and trade”.

Mar

2020

By this time, coronavirus had spread beyond Asian countries and reached Europe - and Italy in particular. Faced with an ever-increasing record of cases, the International Chamber of Shipping (ICS) released a set of guidelines in collaboration with IMO, WHO and other bodies offering advice on port and crew management and health practices.

A day after the WHO declared COVID-19 a pandemic, the IMO announced it would shut its London headquarters as a precaution. At the same time, the organisation also postponed several meetings including the Marine Environment Protection Committee’s review of proposals for better energy efficiency on ships.

Quarantined and locked down, Italy is to date one of the worst affected countries in the world. Struggling with limited availability of intensive care spaces in its hospitals, the country announced in early March plans to turn a passenger ship into a floating hospital to treat the disease.

The ICS and the International Transport Workers’ Federation sent an open letter to UN bodies that read: “In this time of global crisis, it is more important than ever to keep supply chains open and maritime trade and transport moving. In particular, this means keeping the world’s ports open for calls by visiting commercial ships, and facilitating crew changes and the movement of ships’ crews with as few obstacles as possible.”

The UK joined many other European countries in enforcing a nationwide lockdown and closure of all non-essential business. In reaction to this measure, the UK Chamber of Shipping, Nautilus International and the National Union of Rail, Maritime and Transport Workers published a joint statement urging the government to protect the interests of national seafarers. “Our members must be empowered by the government, urgently, to perform the shipping industry's key logistical role in keeping the UK supplied with the food, medicine, fuel and equipment required to sustain people and businesses,” the statement read.

The president of cruise operator Holland America Line Orlando Ashford hit out at international port authorities for their lack of appropriate response to stranded ships at sea – something that he said“tests our deepest human values”. The comments came hours after two ships belonging to the operator – Zandaam and Rotterdam – were finally given the green light to cross the Panama Canal, having been previously refused entry to dock by other Latin American countries. “We are dealing with a ‘not my problem’ syndrome,” said Ashford. “The international community, consistently generous and helpful in the face of human suffering, shut itself off to Zaandam leaving her to fend for herself.”

Apr

2020

The IMO joined many other industry representatives in calling for seafarers and maritime personnel to be recognised as key workers and therefore be exempted from travel bans. In its letter to global governments, the organisation also highlighted the importance of keeping ports open and supporting the supply chain.

As world cases surpassed 1.5 million, the European Commission launched a set of guidelines to support governments when repatriating cruise ship passengers and protecting ship crews. “Seafarers are keeping the vital channels for our economy and supply chains open, as 75% of EU global trade and 30% of all goods transported within the EU are moved by sea,” commissioner for Transport Adina Vălean said. “The guidelines adopted today include sanitary advice, recommendations for crew changes, disembarking, and repatriation for seafarers and passengers.”

A joint statement from the IMO and the World Customs Organization stressed the importance of keeping ports and customs operational to support the supply of essential goods. It came after many hubs around the world started denying entry to ships in fear of contagion. The statement added: “It is critical that customs administrations and port state authorities continue to facilitate the cross-border movement of vital medical supplies and equipment, critical agricultural products and other goods to help minimise the overall impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on economies and societies.

Timeline:

Coronavirus sweeps the global shipping and cruise industries

27

Jan

2020

The first dozen cases of coronavirus were recorded in Wuhan, China, in December 2019. Having registered 25 deaths and over 600 infections in less than a month, in late January the Chinese Government decided to ban ships from entering the Port of Wuhan. On the same day, Singapore started temperature screening procedures at all its port’s checkpoints and several cruise liners cancelled trips to China.

4

Feb

American cruise liner Princess Cruises’ Diamond Princess entered the first day of a long quarantine off the coast of Japan after one of its passengers tested positive for coronavirus. The ship soon became the place with the highest concentration of cases outside of China. Non-affected passengers were not allowed to leave the ship until 19 February - leaving 621 who tested positive on-board.

6

Feb

The fast spread of the virus beyond Chinese borders accelerated preventive measures among its neighbouring port cities and countries. A key step in this direction was Hong Kong’s decision to close its cruise terminals and put all in-bound Chinese travellers into quarantine. Taiwan soon adopted similar initiatives.

10

Feb

Analysis from SeaIntelligence showed container lines were suffering losses of between $300m and $350m per week as a result of decreased traffic. In the space of a week, the study found some 31 new sailings were blanked in the transpacific and Asia-Europe trades in the space of a week.

21

Feb

The International Maritime Organization (IMO) and World Health Organization (WHO) published a joint statement in a bid to ensure “that health measures are implemented in ways that minimise unnecessary interference with international traffic and trade”.

6

MAR

By this time, coronavirus had spread beyond Asian countries and reached Europe - and Italy in particular. Faced with an ever-increasing record of cases, the International Chamber of Shipping (ICS) released a set of guidelines in collaboration with IMO, WHO and other bodies offering advice on port and crew management and health practices.

12

MAR

A day after the WHO declared Covid-19 a pandemic, the IMO announced it would shut its London headquarters as a precaution. At the same time, the organisation also postponed several meetings including the Marine Environment Protection Committee’s review of proposals for better energy efficiency on ships.

13

MAR

Quarantined and locked down, Italy is to date one of the worst affected countries in the world. Struggling with limited availability of intensive care spaces in its hospitals, the country announced in early March plans to turn a passenger ship into a floating hospital to treat the disease.

19

MAR

The ICS and the International Transport Workers’ Federation sent an open letter to UN bodies that read: “In this time of global crisis, it is more important than ever to keep supply chains open and maritime trade and transport moving. In particular, this means keeping the world’s ports open for calls by visiting commercial ships, and facilitating crew changes and the movement of ships’ crews with as few obstacles as possible.”

24

MAR

The UK joined many other European countries in enforcing a nationwide lockdown and closure of all non-essential business. In reaction to this measure, the UK Chamber of Shipping, Nautilus International and the National Union of Rail, Maritime and Transport Workers published a joint statement urging the government to protect the interests of national seafarers. “Our members must be empowered by the government, urgently, to perform the shipping industry's key logistical role in keeping the UK supplied with the food, medicine, fuel and equipment required to sustain people and businesses,” the statement read.

31

MAR

The president of cruise operator Holland America Line Orlando Ashford hit out at international port authorities for their lack of appropriate response to stranded ships at sea – something that he said “tests our deepest human values”. The comments came hours after two ships belonging to the operator – Zandaam and Rotterdam – were finally given the green light to cross the Panama Canal, having been previously refused entry to dock by other Latin American countries. “We are dealing with a ‘not my problem’ syndrome,” said Ashford. “The international community, consistently generous and helpful in the face of human suffering, shut itself off to Zaandam leaving her to fend for herself.”

2

Apr

The IMO joined many other industry representatives in calling for seafarers and maritime personnel to be recognised as key workers and therefore be exempted from travel bans. In its letter to global governments, the organisation also highlighted the importance of keeping ports open and supporting the supply chain.

8

Apr

As world cases surpassed 1.5 million, the European Commission launched a set of guidelines to support governments when repatriating cruise ship passengers and protecting ship crews. “Seafarers are keeping the vital channels for our economy and supply chains open, as 75% of EU global trade and 30% of all goods transported within the EU are moved by sea,” commissioner for Transport Adina Vălean said. “The guidelines adopted today include sanitary advice, recommendations for crew changes, disembarking, and repatriation for seafarers and passengers.”

17

Apr

A joint statement from the IMO and the World Customs Organization stressed the importance of keeping ports and customs operational to support the supply of essential goods. It came after many hubs around the world started denying entry to ships in fear of contagion. The statement added: “It is critical that customs administrations and port state authorities continue to facilitate the cross-border movement of vital medical supplies and equipment, critical agricultural products and other goods to help minimise the overall impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on economies and societies.