Feature

Peril on the high seas: the Yemen oil tanker and the menace of oil spills

The Yemen oil tanker crisis serves as a grim reminder of the environmental risks associated with oil spills in war-torn and disturbed regions. Ashima Sharma investigates.

Pumping oil from the FSO Safer to the relief ship, Nautica. Credit: AFP/Getty Images

The ironically named FSO Safer, an oil tanker moored off the coast of Yemen for six years, carried with it the looming disaster of an oil spill. Holding 1.1 million tonnes of oil, the decaying floating production and storage vessel lay afloat in the Red Sea, unclaimed, only to be termed the “ticking time bomb” that could spill its massive cargo at any time.

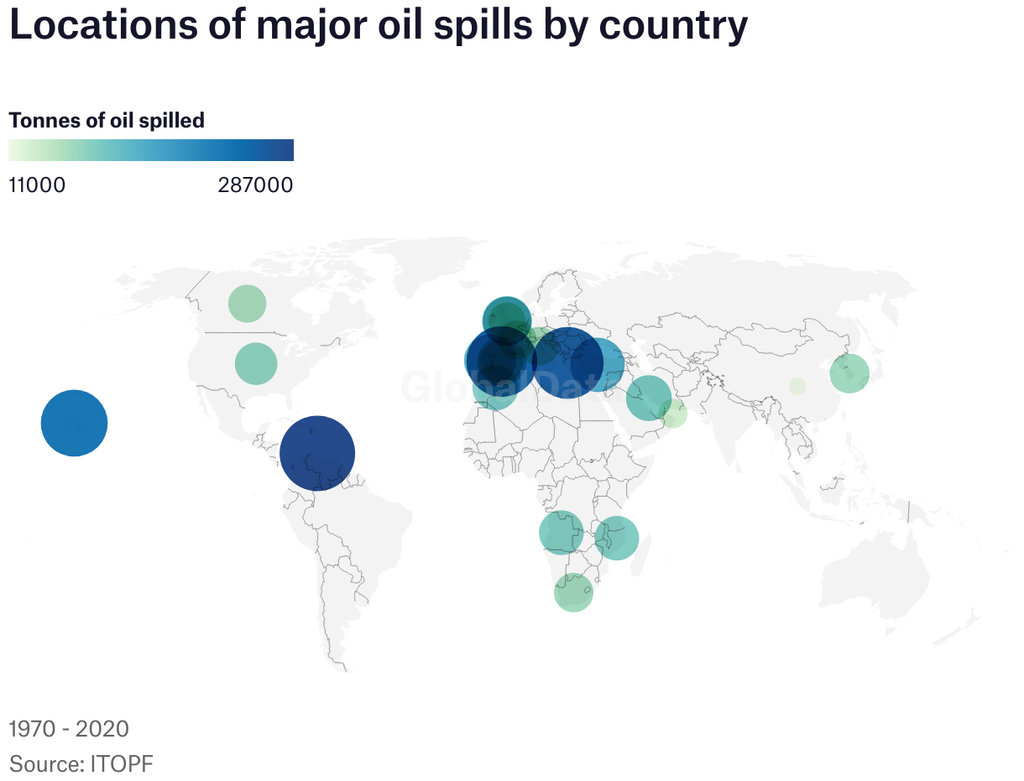

If a spill were to occur, it would be the fifth largest in history. It would have disastrous ramifications for over 17 million people caught in a civil war in the country relying primarily on humanitarian aid. Clean water supply would be disrupted and losing access to fuel would mean shutting down things like hospitals and water systems.

According to the UN, the oil would have slicked to the African coast, damaging 25 years’ worth of fish stock and affecting close to 200,000 jobs in communities that often rely on fishing.

A study by researchers from Stanford University found that the risk of hospitalisation due to cardiovascular or respiratory problems following an explosion would increase by 530%.

And while all these scenarios were highly likely if a spill or an explosion occurred, the disaster was averted in August this year. A team of rescuers pumped between 4,000 and 5,000 barrels of oil from FSO Safer every hour to a replacement vessel, held by the UN.

The rare path away from oil spills

The UN engaged with this potentially catastrophic threat uniquely by raising a crowdfunding appeal to purchase and offload the vessel.

In May 2022, the UN staged a rare donor conference to raise $80m, taking a year to acquire the funds. 23 UN member states funded the mission, with Yemen’s largest private company, Hayel Saeed Anam Group, also donating $1.2m in August 2022.

While one disaster was averted, others await. Even after the transfer, the 47-year-old decaying tanker will “continue to pose an environmental threat resulting from the sticky oil residue inside the tank, especially since the tanker remains vulnerable to collapse,” the UN said. The agency still needs $22m more to finish the job.

Adding to this, the recovery vessel could be stranded until it is decided who owns the oil, and can therefore profit from its sale.

Oil spills caused by war, conflict, and theft represent a distressing reality that exacerbates environmental degradation in some of the most ecologically and territorially sensitive regions.

In countries experiencing conflict, critical infrastructure and oil facilities are often neglected or become targets, leading to spills. Conflicts can also exacerbate the challenges of oil spill response and clean-up.

A potential spill from FSO Safer would have cost $20bn to clean up. The vessel contained four times the amount of oil spilled by Exxon Valdez off the Alaskan coast in 1989, which caused a slick of 1,300 miles.

If one oil tanker can raise such concerns, what next?

The necessary resources and coordination to contain spills are often scarce, leaving local communities and ecosystems to bear the brunt of the consequences. In 2021, a tank filled with 15,000 tonnes of fuel leaked from a thermal power plant in Syria, into the Mediterranean Sea.

Officials at a press conference by Yemen’s Houthi deputy foreign minister Hussein Al-Ezzi about the progress of the FSO Safer‘s oil removal to the new replacement vessel Nautica. Credit: Mohammed Hamoud/Getty Images

For Syria, another country faced with civil war, resources to manage the 800 square kilometre-large spill were meagre. Residents from the town of Baniyas, where the spill occurred, told CNN: “The government only sent teams with sponges and water hoses; they do not have the capacity to deal with this… you cannot clean the sea with sponges.”

Spilled oil forms a slick on the water’s surface that blocks sunlight and oxygen exchange, causing marine life to suffocate. The effects on the smallest animals amplify higher up in the food chain, affecting birds, mammals, and even humans who rely on these ecosystems for sustenance and income.

The Gulf region, where the Yemen oil tanker crisis unfolded, is particularly vulnerable for its rich marine biodiversity and importance as a fishing ground.

Big oil polluters and the impact of vandalism and conflict

Nigeria is a case in point for pipeline vandalism. The country was Africa’s largest oil producer, dropping to its fourth in 2022 according to the International Energy Agency. Nigeria loses an average of 470,000 barrels of crude per day to theft and pipeline vandalism.

The National Oil Spill Detection and Response Agency of Nigeria has estimated that oil companies have lost NGN803bn ($1.04bn) in crude oil to spills suspected to originate from sabotaged pipelines and operational issues in 2022. The country lost NGN362bn ($470m) in 2020, and NGN674bn ($870m) in 2021.

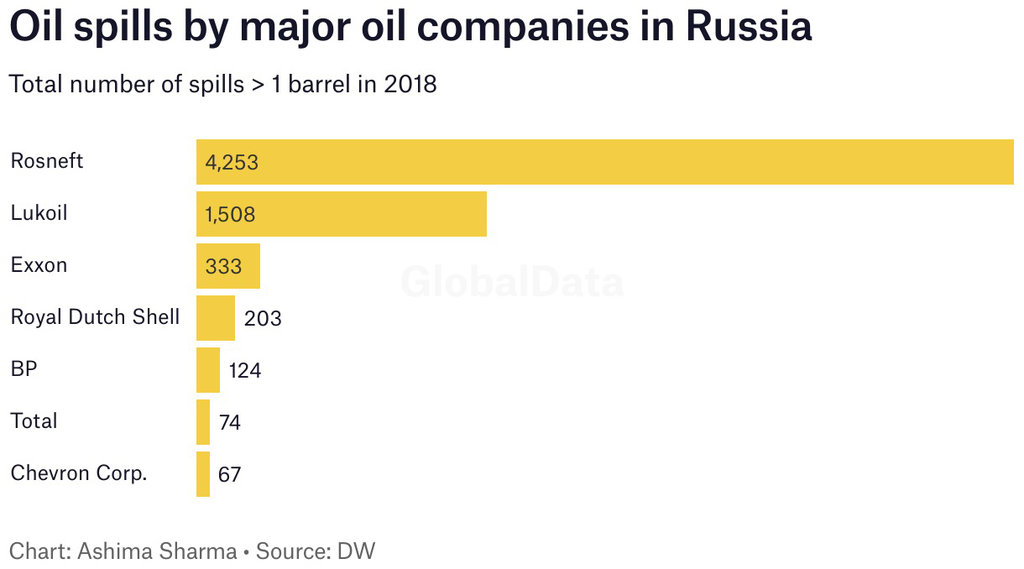

In the Arctic, the biggest oil spill came from Russia in 2020. When a fuel storage tank at Norilsk-Taimyr Energy’s Thermal Power Plant failed, it flooded local rivers with up to 17,500 tonnes of diesel oil. Russia also has an unruly history of oil spills.

According to Russia’s Ministry of Energy, there were over 17,000 leaks in 2019, mostly from pipelines. This data suggests that an oil spill happens somewhere in Russia almost every half hour.

Presently, Russia presents a unique challenge and a threat of spills since its invasion of Ukraine. With Western sanctions affecting the movement and use of Russian crude, big oil insurers have warned of Russia’s “shadow tankers”, that move without third-party liability cover from “well-tested” insurers.

This means that traders with less experience are now moving crude over longer routes in less suitable vessels with unknown insurance provisions. With shadow or ghost fleets now carrying Russian oil, the threat is multi-fold on risk and accountability of a potential spill.

The interplay between conflicts, theft, and oil spills is a sobering reality that exacerbates environmental challenges in regions already grappling with instability. People in Iraq are still reeling under the impact of an intentional spill by Iraqi forces in the 1991 Gulf War.

Iraqi forces leaked over 240 million gallons of oil into the Gulf, and upon retreat from Kuwait, set more than 700 oil wells ablaze. The spill caused a nine-mile slick in water and led to the formation of nearly 300 oil lakes in a desert. In 2021, The Guardian reported that 30 years on, the country still battles with polluted water and contaminated soil.

The Yemen oil tanker crisis serves as a clear and present reminder of the grave environmental risks associated with oil spills. These disasters can wreak havoc on marine ecosystems, livelihoods, and human health, making them an international concern.

Those who clean the spills, as in the case of people who were hired to clean up for BP’s Deepwater Horizon explosion, today suffer from cancer and other illnesses owing to toxins in the oil. Years on, the environment and every person in it continue to take a silent hit in a conflict-oil spill nexus.