FUELS

Greener fuels: Is shipping heading in the right direction?

Climate change is high on the agenda for most countries as they look to reduce greenhouse gas emissions significantly over the coming years. The shipping industry is currently one of the biggest polluters, but it is responding to the need for lower carbon emissions and, ultimately, green fleets. Alex Love speaks to experts leading the quest for new fuel sources that are not only less damaging to the environment but also protect hauliers’ profits.

The shipping industry is facing growing pressure to curb its CO2 emissions. The industry produces approximately 2.6% of all carbon emissions and carries more than 80% of goods traded globally. If the shipping industry were a country, it would be the world’s sixth-highest emitter, ahead of Germany.

US President Joe Biden’s climate change envoy John Kerry has expressed a commitment to ensuring that International Maritime Organisation member countries hit the net-zero emissions targets by 2050. There have also been recent calls within the shipping industry for a carbon tax, which would give companies an incentive to invest in greener technologies and there could be further announcements for shipping in the build-up to the next UN climate change conference, COP26, at the end of the year.

After the 2015 Paris climate change agreement left it to individual nations to cut the environmental impact of their shipping activities, the industry must now make up for lost time.

Slashing the shipping industry’s carbon footprint will require a multitude of solutions. While electric batteries are already starting to play their part for ships on shorter routes, advances in clean fuels are required for larger vessels such as cargo ships and tankers travelling long distances.

However, there is some debate as to which fuel has the most potential, with candidates including ammonia, biofuels, hydrogen, and methanol. If a wide variety of green fuels are developed and put on the market, this potentially risks hauliers arriving at ports that may not have what they need to refuel.

“The real challenge with those fuels is that it's very difficult for a whole industry to decide on one flavour and it's not happening fast enough. It can't happen fast enough, because of the vast infrastructure,” says Diane Gilpin, CEO of Smart Green Shipping (SGS). “It's going to take a long time. And I think that that's a real worry in terms of emissions because they're still rising from shipping.”

Is hydrogen the answer?

Hydrogen doesn't emit any CO2 nor produce sulphur oxides or particulate matter. It can be produced using water and electricity and its green credentials are further enhanced if this power comes from renewable sources. The fuel has a high ratio of weight transported to distance travelled.

Yet there can be storage issues as hydrogen requires either high-pressure tanks when stored as a gas or temperatures of -253°C if a liquid.

Nevertheless, increasing numbers of shipping organisations are viewing hydrogen as their preferred option. The China Maritime Safety Administration has authorised CCS to compile the first national set of technical rules for hydrogen fuel in shipping, while Germany-based energy provider Uniper recently scrapped plans for an LNG import terminal in Wilhelmshaven in favour of hydrogen.

And the technology is already in use. CMB.TECH’s Hydroville is a dual-fuel passenger shuttle that uses hydrogen to power a retrofitted diesel engine to carry people between Antwerp and Kruibeke in Belgium. Injection of hydrogen displaces diesel use. Diesel fuel provides an important backup should there be any issues with hydrogen.

CMB.TECH’S Hydroville is a dual-fuel hydrogen vessel being tested in Belgium. Credit: CMB.TECH.

“Our combustion is very clean and as hydrogen is very easy to combust, it even enhances diesel combustion, so we have a higher efficiency of our engine due to that hydrogen mixing,” says Roy Campe, managing director of CMB.TECH.

Campe explains how Lloyd's Register has performed a full analysis into the design safety of the technology and has verified its use for ships. He adds the transition from fossil fuels to green alternatives should be seen as gradual rather than instant.

“If people say it needs to be zero-emission – okay, if you have deep pockets, we will give it to you. But then we would like to see that every port has not just one refuelling station but also a backup and that there is a significant price disadvantage. I think nobody is willing to pay that last part,” says Campe.

“The first 60% of emission savings are the easiest to achieve. The last 40% is where the costs go exponential and that's where the autonomy falls down. That's why we say the sweet spot is not zero-emission, but dual-fuel.”

CMB.TECH has also developed a tugboat called the HydroTug, which it says is the first 4,000kW class dual-fuel vessel powered by hydrogen and diesel. The company is looking to develop a series of vessels, rather than just one-offs.

CMB.TECH’S HydroTug. Credit: CMB.TECH.

CMB.TECH is now applying lessons learned on smaller ships to larger vessels, building bigger engines up to 2.5MW and is also researching into mono fuel engines. The focus is on achieving commercial viability without depending on subsidies, but to do so will take investment.

“If we are not willing to pay for the hydrogen, then I think we have to stop the energy transition because we are not taking it seriously. If we can't afford it, then we have to question ourselves. Do we want climate change?” adds Campe.

Wind power

Wind is abundant at sea and has been used to propel ships for centuries. Yet this power source has rarely been used for larger vessels since engines became widespread.

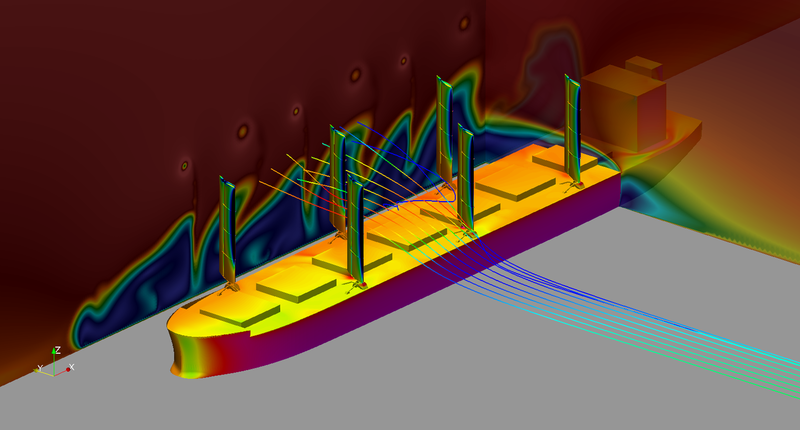

But there are signs of wind making a comeback. SGS’s FastRig involves retractable steel and aluminium sails that provide propulsion for tankers and dry bulk vessels. The company has run detailed simulations through computational modelling involving the Ultrabulk Tiger carrying biomass from Baton Rouge in Louisiana, US, to Liverpool in the UK. Studies found FastRig technology could make noticeable savings in energy consumption.

SGS’s FastRig undergoing computational fluid dynamics tests. Credit: The Wolfson Unit for Marine Technology and Industrial Aerodynamics.

“It's more like an aircraft wing and you might see it on an America's Cup yacht, only it's much more robust and made of metal,” explains Diane Gilpin. “It's a twin element wing so that you can get extra lift from it. But it's automated and intelligent. It's got sensors on it; it knows which way the wind is coming from and what speed it's coming at. So, it will feather and open the wing flap or not according to the conditions it's operating in. If the wind is too great and it's posing a safety risk, it knows to retract so it lies down on the deck.”

Yet despite the potential, SGS has had difficulties securing funding for real-world tests.

“It's a real-world vessel. We've modelled it at real-world speeds and delivery schedules, and we were able to demonstrate we could save at least 20% fuel. That was verified for us by the Wolfson Unit at Southampton University,” adds Gilpin.

“That work is done, we've got a broad cost of manufacture from the analysis we did, but we have to go through a next stage to get market-ready to prove the technology in the real world. And that proves to be hugely problematic, mostly because of a lack of finance.”

Buying time

Ships running on new fuels will likely require retrofitting, and extra room for fuel storage would take up valuable cargo space. However, there may be a solution for both issues, as well as plastic pollution. Clean Planet Energy is turning plastic waste into diesel that meets EN 15940 specifications used by ships. The company can also make fuel oil using this process.

The company only accepts plastic that would otherwise have gone to landfill or been incinerated. CPE doesn’t take PET, which is the easiest to recycle in the circular economy, or PVC due to its chlorine content. But it does accept LVP, HDPE, PP, PE, and PS, with up to 15% contamination. CPE receives plastic from a private contractor and UK councils.

CPE claims its fuel products reduce CO2e emissions by 75% compared with fossil fuels, with minimal SOx and NOx emitted. According to CPE figures, 416kg of CO2e is prevented for every barrel of fuel it produces. In contrast, traditional fossil fuel extraction alone results in an estimated 52kg of CO2 for every barrel.

Clean Plant Energy CEO Bertie Stephens acknowledges that while CPE’s fuels are not a permanent solution to climate change, they have the potential to bridge the gap between fossil fuels and the clean energy of the future.

“Ships have a long lifespan. There's going to be a significant period, 20 years or so, before the large vessels such as freight ships will get to a point where they can utilise hydrogen, for example, on a large-scale basis, which is made in a green way,” says Stephens. “By providing fuels with these sustainability capabilities, we're ultimately buying time.”

Ideally, we would like a world where no carbon-based fuel is used at all.

CPE has two plants currently under construction in the UK. A further four are in development and hoped to begin construction this year. Plants will be capable of processing 20,000 tonnes of plastic per annum, with an eventual combined target of one million tonnes. And CPE’s technology could result in even greater environmental savings, as Stephens explains the company is currently talking to 26 countries around the world.

“Ideally, we would like a world where no carbon-based fuel is used at all. And that theoretically, puts our current business model out of business. That is the best thing for the world,” he adds.

Main image credit: Cameron Venti / Unsplash