ports

port in a storm:

how are maritime hubs preparing for climate change?

In light of recently announced plans for expansion at the Port of Vancouver, some have accused developers of failing to account for climate change in their design. Ross Davies looks at how ports across the world are readying themselves for rising sea levels

when the Roberts Bank Superport was first opened on the Strait of Georgia in Delta, British Columbia, back in 1970, considerations around climate change were non-existent.

Fast-forward 48 years and global warming is roundly identified as the biggest threat facing our planet. As set out in the Paris Agreement, many of the world’s nations, including Canada, have pledged to check global warming at under two degrees.

However, the Vancouver Fraser Port Authority, which includes Roberts Bank, stands accused by Canadian environmentalists of drastically underestimating the potential impact of storm surges and flooding as a result of rising sea levels.

Earlier this year, plans were revealed by the authority to double the port’s size through the creation of a second Roberts Bank terminal. At 1.7km long and 700m wide, and comprised of 18 million cubic metres of rock, gravel and compacted sand, Vancouver Fraser Port Authority claims – rather grandiosely – that Roberts Bank Terminal 2 shall “remain in perpetuity”.

Few can take issue with the new terminal’s central aim, which is to reinforce the port’s standing as a major hub of Pacific shipping traffic. Last year alone, it shifted a record-high 142 million tonnes of cargo, consisting mainly of coal, grain, wood pulp, logs and steel.

The Port of Vancouver is also major contributor to British Columbia’s economy, having generated C$9.2bn and over 40,200 full-time jobs in 2016. With expansion, these figures could increase even further, claims the Vancouver Fraser Port Authority.

Image courtesy of

Storms and stats: the Vancouver Fraser Port Authority defends itself

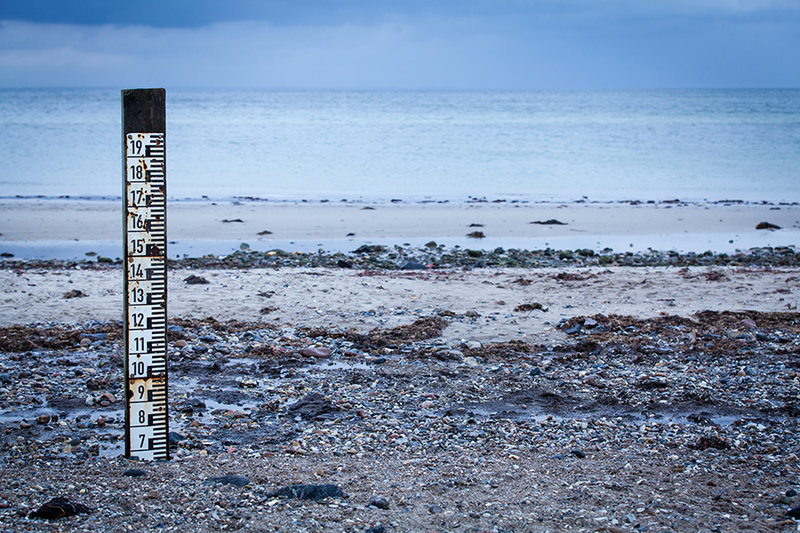

The sticking point is around the terminal’s preliminary design, which forecasts the local sea level to rise by 50cm by 2100. “Sea level rise is not expected to adversely affect the project over the long term,” reads the planning document.

Yet, according to storm simulations conducted by Canadian newspaper The Globe and Mail, if hit by a one-in-500-year storm, much of the port’s facilities would be severely impacted. Throw into the mix a 1m sea level rise expected by 2100, and most of the port would find itself underwater, claims the study.

While the Fraser Basin Council, which supplied the data for the Globe and Mail’s study, declined to comment, the Vancouver Fraser Port Authority rejected any idea that it isn’t taking climate change seriously.

The port authority has designed the project to withstand anticipated seismic activity ... and sea level rise

“The Vancouver Fraser Port Authority is actively addressing the issue of climate change within our jurisdiction,” says a spokesperson.

“Specifically with regard to the Roberts Bank Terminal 2 Project, the port authority has designed the project to withstand anticipated seismic activity, weather phenomena and sea level rise over the lifetime of the terminal, which is beyond 2100.

“This includes designing the terminal to withstand the loads from a 100-year storm event, as well as incorporating a sea level rise prediction of 0.5m.

“With regard to sea level rise, the port authority considered the probability of a 1m sea level rise prediction and a one-in-100-year extreme event occurring during the design life of the project to be quite low. It also determined that a 0.5m sea level rise adjustment to the one-in-100-year estimated design still water level would be considered reasonable.”

The Port of Vancouver

Svein Kleven is senior vice president of engineering and technology for Rolls-Royce. Image courtesy of Rolls-Royce

Growing consciousness: other ports anticipating climate change

The debate taking in place in British Columbia reflects a growing sense of concern as to how the world’s ports can shore themselves up against the risks posed by climate change. In Europe, the Port of Rotterdam is commonly held up as a leader in this area.

While essentially protected against flooding by dykes, and with many of its facilities elevated above sea level, the Port of Rotterdam Authority still chose to recently conduct a joint study – alongside the Municipality of Rotterdam, the Ministry of Infrastructure and the Environment and the port’s private sector – into the potential consequences of climate change and measures to be taken in response.

“I would say that most port operators have begun to consider the future impacts from climate change,” explains Steve Messner, a US-based national expert in energy and climate issues, and founder of e360 Group.

[The Port] is protected against flooding by dykes, and with many of its facilities elevated above sea level

“These risks include damage and loss of activities from increased inundation, greater storm intensities, and increased heat. My experience has been with leaders on the issue ports on the US West Coast and Rotterdam. Other port operators are concerned, but are often limited in what they can do because they operate as landlords and have limited influence over the port tenants with long term concession agreements.”

So what adaptation strategies ought port operators look to enact to protect themselves?

“Some operators are looking into raising wharves and piers, and improving sea wall barriers, but some have been quite limited in what they can do,” says Messner.

“As sea level rise accelerates later this century, this will result in many port operators gaining business or losing business as the differences in cargo and ship safety issues will be more apparent.”

Image courtesy of jan kranendonk / Shutterstock.com

Steep bill: why ports can’t afford not to take climate change seriously

Implementing defence strategies won’t come cheap. According to a recent study by sustainability consultancy Asia Research and Engagement (ARE), upgrading some of the largest ports in the Asia-Pacific region to help cope with the effects of climate chance could cost up to $49bn.

Upgrading some of the largest ports in the Asia-Pacific region could cost up to $49bn

While ARE could not be reached for comment, the report – which accounts for 53 ports found across Japan, China, Hong Kong, Taiwan, Singapore, Australia, India, South Korea and Malaysia – predicts rising damage to ports at the hands of storm surges and disrupted operations. Starker still, if ports don’t stump the cash for climate change protection, operators could face even larger bills in the future.

Put simply, shipping ports have a duty to set in motion appropriate designs and contingency planning. Those that don’t shall do so at their peril.