Ports

Beneath the plimsoll line:

understanding shipping investment

Growing environmental and technological demands are changing the shipping industry, which is increasingly struggling to find investors eager to bet against its volatility. Adele Berti asks: how investment in the sector evolved throughout time, and what lies ahead?

Being responsible

for about 90% of global cargo – according to estimates from the International Chamber of Shipping – the shipping industry has been at the helm of international trade for centuries.

Yet despite its central role, the sector is constantly influenced by external factors, such as political and economic trends, sustainability and technology, making it a historically volatile and unpredictable industry to invest in.

Attracting capital is indeed a constant cause of concern for maritime, which is struggling to get investment for its future vessels in the face of mounting operational and building costs, as well as increasing interest rates.

As more uncertainty looms, experts in the sector give their insight on the dynamics dictating shipping investment, how it has changed over time, and how it will change again in the decades to come.

Stuart Rivers, CEO of Sailors’ Society.

Image courtesy of Sailors’ Society

The evolution of ship financing

“When you're talking shipping investment, there’s kind of two different sides; you've got the owners, and then you've got the finance for the owners,” says Adrian Economakis, COO of automatic identification system and market intelligence service VesselsValue.

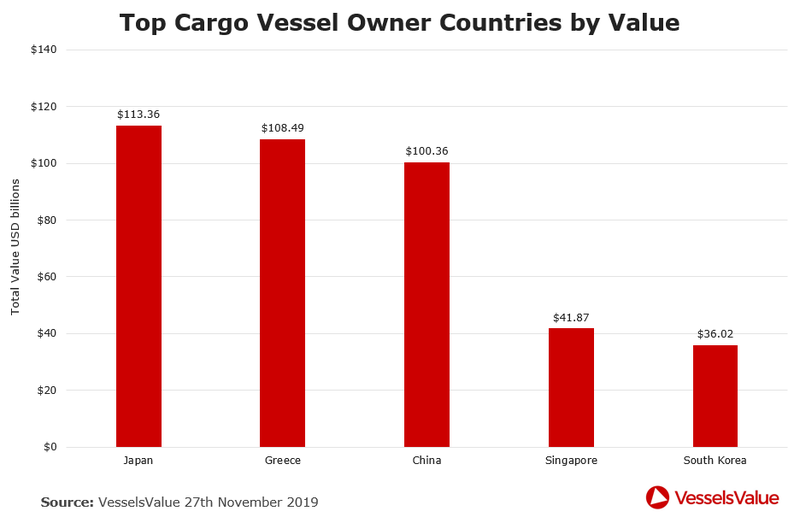

Over the past few years, changes have been happening on both ends. In the owners’ realm, the sector is witnessing the surge of China amidst other more established seafaring countries.

This is according to VesselsValue analysis, which relies on data and algorithm-driven, real-time and historical information about all vessels in the global fleet. Based on this information, the company has compiled a ranking of shipowners, with Greece, China, Japan, Norway and the US in the first five spots.

“The main change over the last ten to 20 years has been the rise of China in terms of the number and value of vessels that it owns,” says Economakis. “So, China has come up that list, while Greece is just about at the top.”

It is, however, on the financiers’ front where most significant changes have been taking place over the past decade or so.

“In the early 2000s, European banks were the primary financier for the shipping industry,” explains Basil M. Karatzas, CEO of international maritime consultancy Karatzas Marine Advisors & Co.

The main change over the last ten to 20 years has been the rise of China

In that scenario, “the shipowner would provide 20%-30% equity and the bank would provide the ship mortgage for the remaining balance at 80%-60% of the value of the vessel, while the shipowner would pledge the vessel itself to the bank in case of a default,” he continues.

Having remained the same for over several years, this model faced an abrupt decline in 2008 due to the financial crisis, which inevitably impacted ships’ earnings as well as banks. Faced with copious losses and the shipping industry’s unpredictability, banks gradually exited the sector. The Royal Bank of Scotland (RBS) was a particularly notable example.

As Economakis explains, “Before 2008, RBS was the largest single lender to the Greek shipowning market in the world, but over the past five years, it has exited its whole shipping business. As the commercial banks moved out, a lot of private equity, particularly in America and elsewhere, moved in to fill that funding gap.”

However, as Karatzas explains, this practice was mostly opportunistic, “as they tried to make money out of the distress of the shipping industry”.

Top cargo vessel owner countries by value as of 27th November 2019. Image: VesselsValue

New players coming in

Yet, having posted substantial losses, private equity and hedge funds are now looking to exit the sector themselves. “Right now, the interest from institutional investors is rather lukewarm,” continues Karatzas, as “they do not have much interest to invest”.

As a result, the sector is witnessing a rise in alternative sources of investment. These include Chinese banks, which are increasingly lending into local and international vessels, as well as technology-based means such as crowdfunding.

In addition, this void is leaving space for the so-called alternative capital funds, which are “funds that are not regulated and can provide financing effectively trying to supplement or substitute the banks' leave from the industry.

Shipping is effectively a game of supply and demand

“So, instead of borrowing from a bank, shipowners can borrow from a fund. However, the interest that funds are charging is 9%, which is much more expensive than the bank typical charge.”

According to VesselsValue’s Economakis, these changes in financing should be seen as a positive sign: “Currently, what the owners will say is that there's a difficulty in getting funding, which actually is quite a good thing for the shipping industry.

“Shipping is effectively a game of supply and demand. If demand goes faster than supply, then the shipping markets improve, earnings go up, values go up and so on.”

This means that despite the slowdown in supply, which is caused by a lack of funding, the supply-demand dynamic will eventually be reinvigorated by it.

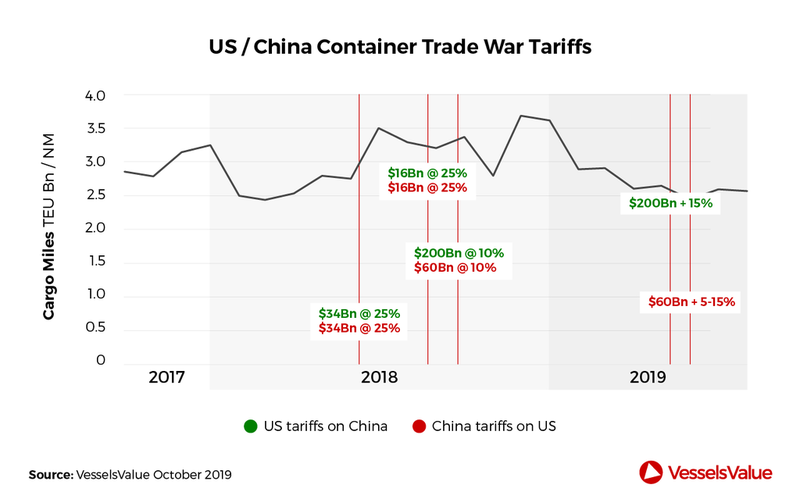

US/China container trade war tariffs up to October 2019. Image: VesselsValue

Rising shipbuilding challenges

New technologies and sustainability are reshaping operations and investment in an unprecedented way. “While in the last 20-30 years, nothing has changed in shipping,” explains Karatzas, “in the last few years, we’ve seen a lot of investment in software and technologies.”

“So, it's no longer the same case as ten years ago, where you were chartering a vessel to move your cargo and didn't really care about the vessels' itinerary. Now, it's more of a case of wanting to know where the cargo is, when it should be expected, the emissions, and how the bank calculates the emissions and cost of capital.”

China's focus on the Hambantota Port is part of its ongoing strategy to build strategic footholds in South Asia

A more connected supply chain, as well as mounting uncertainty on what future vessels will look like, is inevitably affecting the choices made by investors.

As Karatzas puts it, “there is a lot of discussion on the arrival of unmanned ships which again will change completely the industry. So, the vessel that you're building today could look completely different in the next few years and that's another reason for investors having cold feet [about] the industry.”

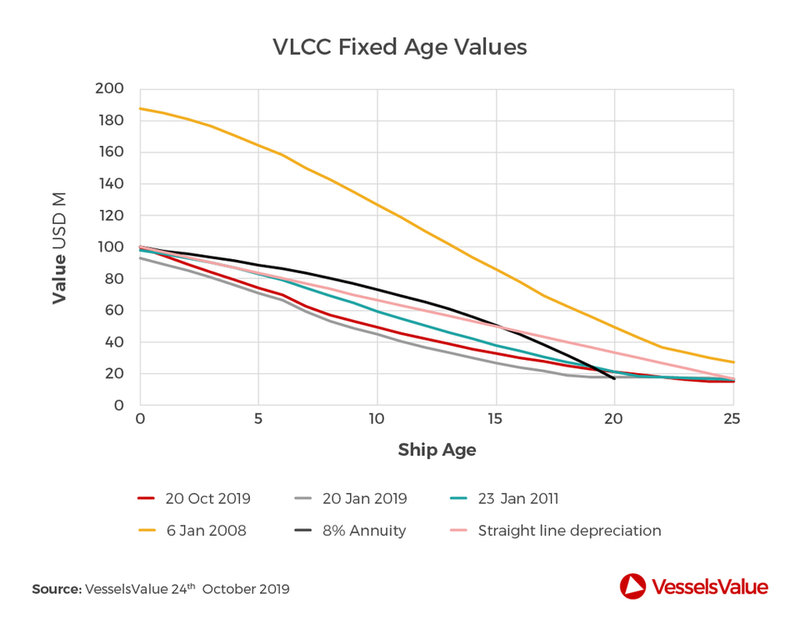

VLCC fixed age values across a number of periods. Image: VesselsValue

The impact of sustainability on investment

Within this framework, the industry’s focus is shifting towards sustainability and efficiency, especially as the countdown to the International Maritime Organization’s (IMO) 2020 sulphur cap reaches an end.

Set to come into force in January 2020, the new regulation will require a cut in fuels’ sulphur content from 3.5% to 0.5%. Alternatively, ship operators can choose to fit their vessels with scrubbers, which pass sulphur oxides through a water stream and remove them from the exhaust gas.

“The environmental impact and efficiency of vessels are now becoming a significant driver to an investment hypothesis,” says Economakis.

A testament to this is the recent Poseidon Principles agreement, which was signed by a number of financial institutions – including Citi, DNB and Societe Generale – looking to align their portfolio with the IMO’s goal to cut 50% of carbon emissions by 2050.

“The preference of lenders to lend on more eco environmentally friendly ships is certainly having an impact on what owners are doing, the types of ships they're looking to build, and the retrofitting of vessels,” Economakis continues.

The environmental impact and efficiency of vessels are now becoming a significant driver to an investment hypothesis

Fitting vessels with scrubbers is indeed proving particularly costly. As Karatzas explains, “a scrubber by itself costs close to $10m, which is almost 10% of the cost of a brand new vessel.

“So for a shipowner who has 10-20 [very large crude carriers], that is a substantial amount of money to spend or invest, and that definitely affects the interest of investors because now you have a new factor that is unknown.”

Yet according to Economakis, such a critical moment for the industry is not altogether negative, as he says: “[IMO 2020’s] positive effect is that it should make the older, less efficient vessels less competitive in the market,” which will then limit the availability of vessels to the most sustainable ones.

Preparing for more radical change

In the decades to come, both Economakis and Karatzas expect these technological and environmental trends to shape investment even more radically than now.

For Karatzas, this will mean following a similar path to what the car industry has been witnessing over the past two decades, as “most vessels will be operated by GPS and satellite”, as well as “fully automated, standardised and more dependent on software rather than hardware”.

In addition, VesselsValue expects demand for liquefied natural gas (LNG) to skyrocket as it is used to support a much larger proportion of global trade.

Alongside LNG, the industry is already focusing on building dual-fuel vessels, as well as fitting them to be hybrid or powered by hydrogen and ammonia.

Alongside LNG, the industry is already focusing on building dual-fuel vessels

“We very much see more preference [of] eco-type lending and investment in vessels,” he continues, adding that “much farther off, we'll probably see more and more use of technology for the technical and commercial operation the vessels.”

Finally, he concludes, as the industry embarks on the digital revolution, increasing interest will be directed on backing the commercial operation of vessels by analysis and data, which will “optimise the purchasing and commercial management of vessels”.