Regional focus

The Port of London: a century of change

Trade through the Port of London hit 53.2 million tonnes last year, a remarkable feat last achieved over a decade ago. Adele Berti goes back in time to explore how one of the oldest ports in Europe has evolved, from hosting steamships of the early 20th century to the bustling enterprise it is today.

Image courtesy of PLA

Stretching alongside

the River Thames from London to the North Sea, the Port of London has for centuries been a great catalyst for trade and growth for both the English capital and the rest of the country.

One of the oldest and most famous ports in Europe, it has proved to be of crucial help for national and international markets since the Roman Empire, supporting Britain’s hugely successful history of maritime trade.

As time goes by and the UK dives into the uncharted waters of Brexit and growing environmental constraints, the port has once again been called to play its part. And having recently witnessed a ten-year high in trade through the hub in 2018 and the decision to adopt the UK's first hybrid pilot boat, it may well be on route to meeting expectations.

With a prosperous future ahead, the Port of London has come a long way to secure its position as a leading hub in the global maritime market. Here is a look at its fascinating – though often troubled – history and the most significant milestones it reached over the years.

Stuart Rivers, CEO of Sailors’ Society.

Image courtesy of Sailors’ Society

From the Romans to the industrial revolution

Early trading activities of commercial shipping routes alongside the Thames date as far back as Roman times, during which maritime trade was identified as a pillar of the city’s economic, financial and political growth.

From the Normans to Queen Elizabeth I, whether for commercial or military purposes, the hub became the beating heart of the city and always managed to adapt to changing technologies.

In this sense, a turning point was marked by the advent of the steamship in the early 19th century, which increased the tonnage of vessels through the port.

This transition process took the best part of the century; it wasn’t until 1875 that steam overcame sail, representing 5.1 million tonnes handled compared to sail’s 3.6 million tonnes.

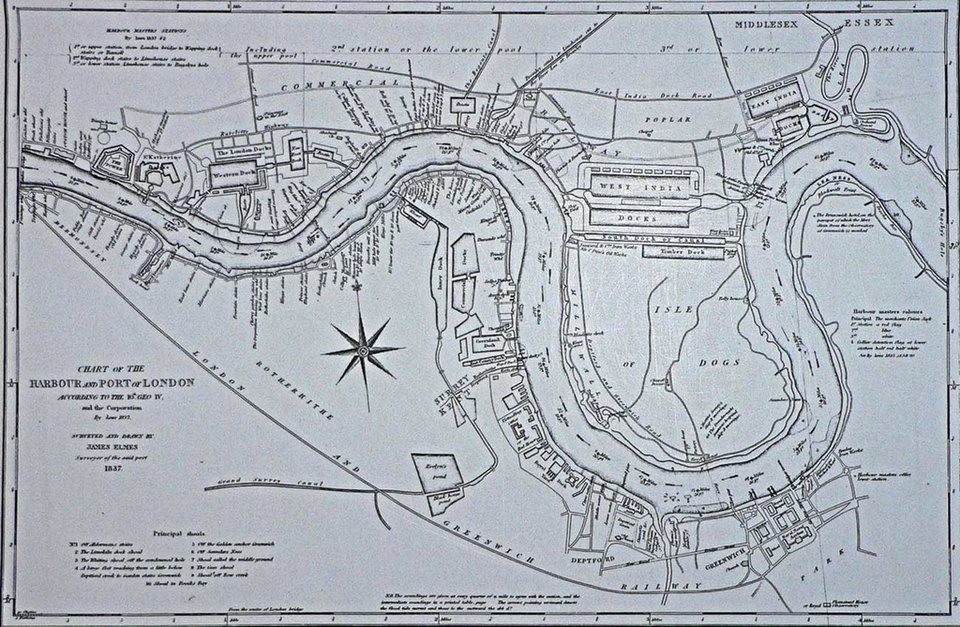

The port at the beginning of Queen Victoria’s reign in 1837. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Early trading activities of commercial shipping routes alongside the Thames date as far back as Roman times, during which maritime trade was identified as a pillar of the city’s economic, financial and political growth.

From the Normans to Queen Elizabeth I, whether for commercial or military purposes, the hub became the beating heart of the city and always managed to adapt to changing technologies.

In this sense, a turning point was marked by the advent of the steamship in the early 19th century, which increased the tonnage of vessels through the port.

This transition process took the most part of the century; it wasn’t until 1875 that steam overcame sail, representing 5.1 million tonnes handled compared to sail’s 3.6 million tonnes.

1902 - 1909

The birth of the Port of London Authority

With the kick-off of the 20th century, the Port of London faced a number of problems – including high charges and damaging internal competition – that threatened to jeopardise its role within the country’s growing empire.

In 1902, further congestion issues and worsening rivalry among wharfs, docks and river eventually persuaded a Royal Commission that a unified port authority was needed to handle movements to and from the Thames.

Seven years later, the Port of London Authority (PLA) was born under the Port of London Act 1908; formally introduced by then Prime Minister David Lloyd George, it was ultimately implemented by Winston Churchill.

Former Port of London Authority building in Tower Hill, London. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

1910 - 1921

The PLA gives new life to the port

The establishment of the PLA proved fruitful for the port. In its first full operating year, some 18.6 million tonnes of cargo were operated by the trust, with almost 10,000 vessels using its docks.

On the verge of the First World War, the hub also kicked off a programme of deep river dredging and dock improvements that culminated with the inauguration of the King George V Dock in 1921. This addition made the Royal Docks complex the largest in the world.

Maintenance works and updates continued during the Great War and the port helped keep a stranded Britain going despite reduced manpower and scarce trading opportunities.

Caption. Image courtesy of

WWII

The port at war

The hub reached one of the most important milestones since the creation of the PLA when it registered a record 44.6 million tonnes of overseas and coastwise import and export cargoes in 1938.

As the Second World War broke out, the Royal Navy established guard ships and oversaw the manning of batteries around the river and near London’s industrial areas.

But nothing could ever prepare the port to face the onslaught of bombings that started in September 1939, destroying several docks.

Yet despite the persisting attacks, the hub was crucial in supporting preparations for the D-Day landings on 6 June 1944, the 75th anniversary of which was recently commemorated in Portsmouth and Normandy.

The port at war. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

60's - 80's

The slow downfall of upriver enclosed decks

After a quiet post-war decade, during which the hub introduced new sophisticated technology to improve navigation, the PLA cruised through the 1960s with positive signs of growth.

It was in 1964 that the port handled its largest ever annual throughput of over 60 million tonnes.

The economic boom also meant expansion and new opportunities for the authority, which received, in 1969, the first transatlantic container vessel.

However, the rise of larger ships and significant changes in cargo handling technology also marked the slow end of the upriver enclosed docks, which were progressively closed between the late 1960s and the early 1980s.

The London docks in 1962. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

1990s

A decade of changes for the Port of London

The dock’s closures opened up new possibilities for the PLA, which used its funds to inaugurate a brand-new £3m main office at Gravesend in 1992. The building and the nearby Royal Terrace Pier are still today the management base for PLA’s river operations.

However, the end of the decade proved challenging. In 1998, the planned closure of Shell’s Haven refinery – which contributed 15% of the PLA’s revenues – forced it to roll out a programme of cost savings.

The following year, the hub also had to transfer responsibility of its passenger river piers to the London River Services, as part of the newly-formed Transport for London.

Caption. Image courtesy of

2009

The PLA turns 100

The PLA celebrated 100 years since its establishment in 2009 with a number of events that included a centenary concert at Cadogan Hall, the publication of a centennial history and an exhibition at the Museum of London Docklands.

A lot has changed since its foundation. Over the years, the PLA has survived two world wars, seen the dawn of its enclosed systems and ceased its involvement in cargo handling.

The self-funded trust now employs 360 people and is primarily in charge of maintaining and supervising navigation.

The PLA’s centenary concert at Cadogan Hall, London. Image courtesy of PLA

2014 - 2018

Trade hits a ten-year high

As we prepare to start a new decade, the Port of London can salute the one about to end with a positive outlook.

In the years leading up to 2019, the hub has managed to welcome the largest container ship to run on the Thames. At nearly 400 metres long, the Edith Maersk called at London Gateway in 2014. The following year, the river also hosted its biggest-ever cruise ship, the Viking Star.

As of last year, the Port of London enjoyed a particularly florid period of growth, which brought trade to a ten-year high of 53.2 million tonnes.

Looking ahead, the hub is expecting cargoes on the river to grow to 80 million tonnes by 2035.

Image courtesy of PLA