Ports

Sounding:

the evolution of hydrographic survey methods for ports

Belgium’s Port of Antwerp has commenced the trial of a fully automatic sounding boat named Echodrone. What is the importance of sounding, and how is this practice set to evolve in the future? Joe Baker finds out

Image courtesy of

At the world’s busiest

ports and harbours, ensuring that maritime operations can continue safely is not just about the operations above the water’s surface, but also below it.

Many ports around the world suffer from the impact of siltation, which is the build-up of silt and clay brought in by ocean tides and deposited on sea beds. In addition to damaging marine environments, this build-up can decrease the depth of vital maritime channels and cause potential safety issues for deep-hulled container vessels departing from or arriving at ports.

As hydrographic survey technologies have improved, so too has port authorities’ ability to map out the seafloor and plan future dredging operations to combat siltation. Sounding encompasses the methods used to measure water depths and has come a long way since sailors first began exploring the concept.

Stuart Rivers, CEO of Sailors’ Society.

Image courtesy of Sailors’ Society

A brief history of sounding

Back in the 1800s, hydrographic surveys required sailors to chuck sounding poles and weighted ropes overboard until they hit the seafloor, before cross-referencing this with pre-established points on a map. An early 20th century method involved dragging a weighted wire underwater between two or more vessels to see if it hit any obstructions.

Thankfully, new solutions have emerged to replace these labour-intensive and time-consuming practices with more accurate sonar (or sounding) technologies.

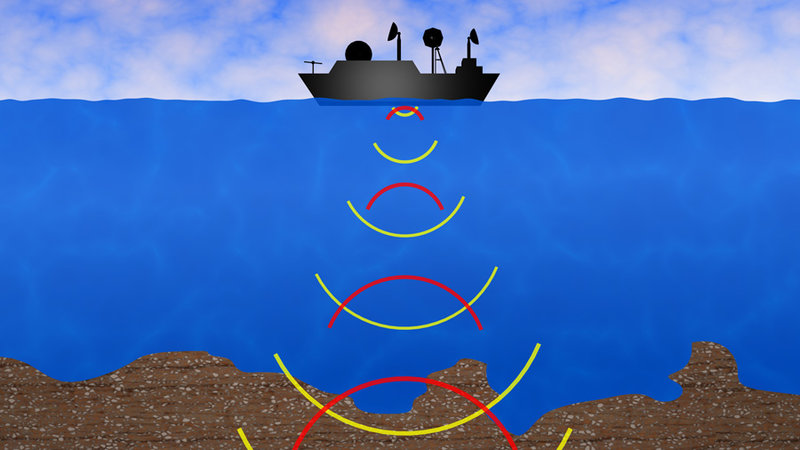

Single-beam echo-sounders (SBES) first emerged in the 1930s and have since become a mainstay for identifying the depth and topography of seafloors. These revolutionary systems determine water depth by measuring how long it takes a short sonar pulse, also known as a ‘ping’, to travel to the sea bottom and back to an emitting source. In most cases, a transducer is suspended underwater from a vessel above.

Multi-beam echo-sounders are capable of mapping various points in a single ping

SBES have become a mainstay for surveys and over time, have grown to become compatible with an increasing number of modern-day technologies. The SEBS offered by CEE HydroSystems, for example, provides Bluetooth and Wi-Fi connectivity, an internal recording system and advanced built-in GNSS and GPS receivers.

In addition, since the 1950s, scientists have built on this concept even further. Multi-beam echo-sounders that are capable of mapping various points in a single ping have been developed. Side scan sonars, meanwhile, emit conical or fan-shaped pulses across a wider area, allowing surveyors to create a more accurate image of the seafloor and highlight the differences between materials.

Image courtesy of

Image courtesy of

Autonomous vehicles for sounding

Ports are now looking into whether autonomous drones could be used to carry out sounding in lieu of survey boats, speeding up the process and making them more compatible with busy shipping schedules.

The leader of the hydrographic survey team at the port of Antwerp, Kurt Stuyts, says that sounding is a hugely important process for planning maintenance works. Until this year, the port has deployed its Echo survey ship, equipped with an MBES system, to carry out the task. However, finding the time to weave a survey ship through Europe’s second largest port is no easy feat.

“It all starts with the problem of busy berth places in the Port of Antwerp,” says Stuyts. “We have one dock that is so busy that when one ship leaves, the other is standing ready to take the berth again and in between we don't have the time to do the survey.”

In response to this problem, Antwerp announced this year it would be adding a new autonomous sounding drone to its growing portfolio of smart solutions. Developed alongside cloud-based navigation specialist dotOcean, the Echodrone system is currently undergoing trials in the hope it could one day patrol the port’s Deurganck dock, which accommodates an annual freight volume of nine million TEU.

With its smaller size and ability to operate autonomously, the Echodrone will be able to dip in between heavy shipping traffic, enabling 24/7 survey operations and increasing accessibility around the port. Speeding up this process would cut costs, as the port would no longer need to pay survey staff to wait around until they have a clear path.

Antwerp announced this year it would be adding a new autonomous sounding drone to its portfolio of smart solutions

dotOcean co-founder Koen Geirnaert says that Echodrone’s unique cloud-based system represents a unique new approach to autonomy. Navigation data collected from sensors around the port of Antwerp is made available over the internet, before being translated into useful information by cloud algorithms. The vessel is able to use this verified data to move around the port, unlike standard autonomous drones which rely on on-board sensors. In the future, data collected from manned vessels could be compiled into the cloud as well.

“If you look in the market, most of the vendors start from building ears and eyes on the vessel itself,” says Geirnaert. “Our approach has been more holistic in the sense that the eyes and ears are coming from the environment in which the vessel is operating, which means you can anticipate actions because you know the information much more in advance than if you retrieve it from a local point.”

In addition to navigation data, sounding data from the Echodrone can be shared from the cloud to the main Echo vessel, which is then able to map the seafloor. “It gives the advantage that you have a single database where you can store and track all your movements and all your collected data,” Geirnaert says.

At the time of writing, Echodrone is undergoing object avoidance trials, while docking, decision-making and windows of operation will represent further challenges in the future. However, Stuyts says that the multipurpose nature of the vessel means it could be equipped with other survey equipment, such as laser scanners, water samplers and a system for photographing quay walls.

“We are seeing if it’s possible to test it with plastic catchers, so we can clean up the port of Antwerp while we are surveying,” he adds.

Image courtesy of

Next steps for hydrographic surveys

Sounding has certainly come a long way, but further improvements to technology could make it even easier in the future to find out what lurks under the sea. From a port perspective, this means safer operations and, in the case of Antwerp, a less frustrating task.

Stuyts also mentions that new technologies, such as artificial intelligence, could be used to help improve hydrography in the future.

In particular, finding new ways to better recognise different materials and objects underwater could further enhance dredging operations, as costs can differ depending on what is being dredged (i.e. silt or sand) and what debris might be laying on the seabed.

It’s important that we know what kind of solid is going to be dredged before we start

“We are still learning much more about the backscatter from multibeams so we can take more info about materials on the bottom,” says Stuyts. “It’s a very big task for our surveyors to check all the data if there’s something on the floor, so when a computer can take over, it will again save time.”

“It’s more and more important for the dredging operations that we know what kind of solid is going to be dredged before we start, especially for knowing what to do afterwards. That's something that we’re looking for in the future and where a lot of players are aiming their efforts.”