Operations

The 80/20 rule:

optimising voyages to improve vessel performance

According to voyage intelligence specialist StratumFive, shipowners are at risk of over-investing in voyage optimisation solutions that don’t account for the impacts of weather at sea. Why is weather forecasting and route optimisation shippers’ best bet when it comes to optimising vessel performance? Joe Baker finds out

Image courtesy of

Just-in-time supply chains,

rising fuel costs and environmental impacts have all increased pressure on shipping companies to optimise their shipping voyages. But what does this mean, exactly?

For major players in the maritime industry, it means on-board technologies that identify the best areas for cutting fuel consumption. Last year’s Vessel Performance Optimisation Forum, held in Copenhagen, saw a number of industry experts gather to argue about the best ways to design and maintain ships to improve vessel performance.

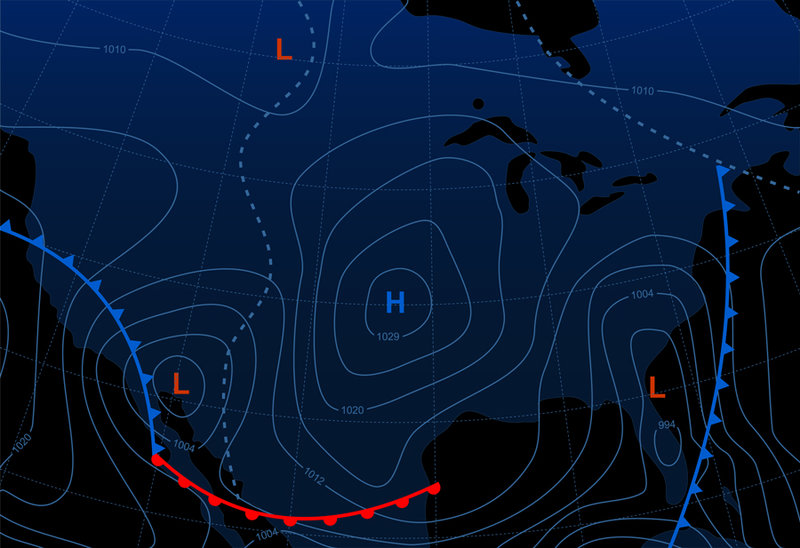

However, some industry spectators argue that squabbles over the best ways to design vessels has drawn focus away from the greatest enemy to progress on the open seas: the weather.

Earlier this year, voyage intelligence specialist StratumFive claimed that the industry risks spending swathes of cash on optimisation services that fail to increase overall efficiency, because they don’t account for the impact of weather on voyages.

The company’s CEO Stuart Nicholls went as far as applying the Pareto Principle to ship performance, saying that the combined effects of weather impact vessel performance in a proportion of 80%, while other factors count for the remaining 20%.

“If you put your ship in the wrong place, none of the other stuff matters,” says StratumFive principal of meteorology Huw Davies. “The power of the ocean is extraordinary.

"One Atlantic storm has more power than all the bombs dropped during WWII. So don’t put your ships in the wrong place and then you won't have to tinker around the edges with trim and engine settings.”

Davies says that while shipmasters can’t control the weather, modern forecasting methods and data allow them to identify levels of resistance as a result of weather factors and optimise their routes to avoid adverse conditions. But why is this notion being swept under the rug and what can shipping companies do differently?

Stuart Rivers, CEO of Sailors’ Society.

Image courtesy of Sailors’ Society

The impact of weather on resistance

Davies says that ships have not become any more resistant to weather conditions at sea. If anything, the growing size and nature of modern container ships has made them more susceptible to the elements.

Container ships’ mind-boggling scale and box-shaped designs allow them to maximise cargo on-board, but can also land them in trouble during harsh weather. One such hazard is parametric rolling, a phenomenon whereby container ships experience a large unstable roll motion in choppy water. This can cause container loss, damage to machinery, or in the worst cases, ships can capsize.

“It’s not true that ship design has really moved on to make ships more sea-kindly or improve their handling,” Davies says. “Extreme weather is happening more often – and it’s extreme weather that poses the most danger to vessels.”

Extreme weather is happening more often, and it’s extreme weather that poses the most danger to vessels

Indeed, extreme weather is on the rise as a result of climate change and it has persistent consequences for the shipping industry. Statistics from the International Union of Marine Insurance (IUMI) indicate that weather accounted for 48% of total shipping losses from 2011 to 2015, and 25% of total shipping losses over the longer timeframe of 1996 to 2015.

Currents, waves and wind work against vessels to some extent on every voyage. Of particular importance here is the slip: the ratio between the distance the ship should have covered, compared to the distance that it actually covered. The more resistance a ship runs into, the more fuel it will consume.

StratumFive claims that resistance when navigating in unfavourable conditions generally increases by 50-100% of the total ship resistance in calm weather. Davies highlights an example of a tanker voyage between Amsterdam and Gibraltar in 2015. The tanker sailed into the teeth of a severe gale in the English Channel, but by sailing a day later she would have experienced a lower sea state, used a third of the fuel, and would have still arrived at the same time.

Image courtesy of

Image courtesy of

Meteorological uncertainties

If this is such a big issue, why are shipping companies still not properly considering the impact of weather on voyages and planning journeys accordingly?

Modern meteorology has improved in leaps and bounds, with numerical weather prediction (NWP) creating more and more accurate predictions based on computational models. However, Davies says that the availability of NWP data and its ease of display on computer systems means that people are used to seeing weather forecasts from multiple sources and not questioning their reliability.

A prime example is the El Faro disaster in 2015, which resulted in more than 30 casualties at sea. At a US Senate committee earlier this year, it was proposed that the ship’s captain may have moved the ship into the path of Hurricane Joaquin after reading outdated weather information.

Marine academies have not caught up yet with the advances made in meteorological broadcasting

“Weather forecasts, because [they are] ubiquitous, have become somewhat devalued because people can get them free, but they don't appreciate that they might be rubbish,” says Davies.

“There is a safety of life at sea [SOLAS] issue and weather is covered by SOLAS, but marine academies have not caught up yet with the advances made in meteorological broadcasting. There are a lot of [weather] companies that do not attribute the data they get to the model that’s produced it.”

Image courtesy of

An ‘antagonistic’ relationship

Another possible concern is a lack of transparency in the relationship between many charterers and shipping companies, which Davies says can be “antagonistic”.

In addition to coughing up for marine fuel, charterers are often commodity brokers selling wares whose prices constantly fluctuate on the stock market, making it extremely important that vessels arrive on time.

Shipowners may be incentivised to overestimate the speed of their vessels to make themselves more attractive to charterers, but this can result in shipmasters having to move at impossible speeds, leading them to overestimate weather conditions so they don’t have to comply with their contracts.

Charterers then hire a weather specialist to monitor conditions based on daily ship reports. But this can cause mistrust between parties.

“The problem is the weather company is working for the charterer,” says Davies. “So there's a lot of dispute about this at the end of voyages and it runs to hundreds of thousands of dollars.”

China's focus on the Hambantota Port is part of its ongoing strategy to build strategic footholds in South Asia

Image courtesy of

Route optimisation for vessels

On-board solutions are popping up to assist with route optimisation. Earlier this year, MeteoGroup introduced the latest version of its Ship Performance Optimization System (SPOS), which the company says calculates routes while anticipating upcoming weather and sea conditions.

Davies says the best option is to use weather and ship data from past voyages to identify how ships will perform in a variety of weather conditions. Since March, StratumFive has been trialling a new process that uses machine learning to build predictive models for weather forecasting.

This process begins with estimates of wind resistance, waves and currents on generic laden and ballast ships. The company then reconstructs an individual vessel’s past voyages and ‘takes out’ the impact of these factors to leave the ‘true’ performance of the vessel.

“We repeat this process many times to refine the estimated weightings over time using supervised AI learning to create a unique set of performance weightings unique to each vessel,” says Davies.

StratumFive has been trialling machine learning to build predictive models for weather forecasting

“We can now apply this ship performance characteristic to the forecast weather predictions, so we can accurately predict the performance of a ship on several routes in the future and create the optimum route based on that analysis, which is now unique to that ship.”

The upshot of this process is that it could solve the potential transparency issues between shippers and charterers. By proposing a realistic estimate of consumption and vessel speed based on forecast conditions, charterers are provided with realistic costs and estimated times of arrival, while shipmasters can concentrate on vessel performance. They could even negotiate a ‘gain-share’ agreement, under which any savings made by the master as a result of a speedier journey could be split evenly between them.

“They will be able to make trade-offs before the voyage,” says Davies. “There are occasions when a chartered vessel can arrive on time or arrive within the fuel allowance, but you can’t do both. It is better for charterers and owners to expose these situations beforehand.”