Shipbreaking

Ship recycling:

can Europe clean up its own mess?

With a Chinese ban on scrapping EU-flagged ships, and a new shipyard regulation set to come into play at the end of the year, shipowners on the continent are concerned about diminished recycling capabilities. But is their reaction justifiable or overblown? Ross Davies takes a look at both sides of the argument

Image courtesy of

For decades,

the European shipping industry has taken its decommissioned vessels to China to be recycled.

But from 1 January 2019, shipowners on the continent will need to find an alternative scrapping destination. As announced in May, the Chinese Government added old ships to its growing list of prohibited imports.

Beijing claims it has implemented the ban in the name of environmentalism, but this has done little to appease European shipowners, who fear the embargo will drastically reduce their options when it comes to recycling.

The start of the ban also coincides with the introduction of the 2013 European Ship Recycling Regulation, which aims to make the recycling of ships in Europe both safer and more environmentally sound. Shipyards that fail to comply with the standard will be removed from the European list of ship recycling facilities.

However, there are fears within the industry that China’s retreat, together with the new regulation, could drastically cut recycling options for EU-flagged ships. This has been the theme of recent meetings in Brussels, attended by member states’ shipping experts, who believe the standard should be relaxed in order to allow more beaching yards to be granted approval.

Stuart Rivers, CEO of Sailors’ Society.

Image courtesy of Sailors’ Society

A move in the wrong direction: the implications of China’s ban and new rules

As the world’s largest shipping association, the Baltic and International Maritime Council (BIMCO) was one of the founding fathers of the 2009 Hong Kong Convention for the Safe and Environmentally Sound Recycling of Ships. The new EU regulation is considered to be a continuation of this convention.

Peter Sand, BIMCO’s chief shipping analyst, believes the new rules aren’t helpful, and the industry would do better to focus on the Hong Kong Convention, to which France is currently the only EU member state to have signed up.

“The shipping industry is global and so it should remain, avoiding local and regional authorities to bias the playing field,” he says. “I believe promoting the Hong Kong Convention, which seeks to improve facilities globally, is the way to go forward – even if implementation of that still seems to be somewhere in the future.

The shipping industry is global, and so it should remain

“The move by China to limit the international owners from demolishing ships in China is a move in the wrong direction.”

Another factor that needs to be taken into consideration, adds Sand, is the current high demand for scrap steel – the main by-product from commercial ship recycling.

“This is not a matter of passing the problem on to someone else, but there are currently no EU facilities on the white list for owners to go to,” he says. “Moreover, the ltd-price in the open market for scrap steel coming from ships is naturally higher in India, Bangladesh and Pakistan than it will be at a facility in the EU.”

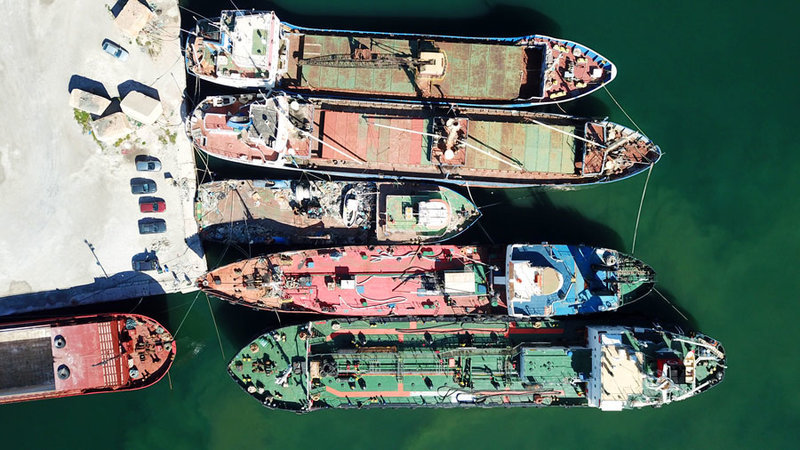

Image courtesy of

Image courtesy of

What capacity crisis? The case for the new EU recycling regulation

Ingvild Jenssen, founder and director of the NGO Shipbreaking Platform, disagrees. While appreciative that closed access to Chinese yards is “a pity”, she believes the 21 EU-based facilities currently on the list are more than capable of recycling European end-of-life fleet.

“The capacity problem is a clear red herring,” she says. “It is a disgrace that shipowners spend more time coming up with bad excuses not to follow legislation – which was agreed upon in 2013 and will make ship recycling a much cleaner and safer practice – than finding alternatives to the dangerous and polluting practice of beaching.

The capacity problem is a clear red herring

“There is capacity in the EU to recycle ships properly, and the yards on the EU list can take in many more – and larger – vessels than what they recycle today. It boils down to not accepting the profits made when selling to yards that ignore occupational safety and environmental protection standards.”

According to Jenssen, shipowners are refusing to countenance clear options right in front of them, citing yards in Italy and Norway which are expected to be included on the list before their application comes into play.

There are also other options outside the EU, although she draws the line at Indian beaching yards, which have applied to be included on the list: “There is no way for these yards to comply with the requirements as long as ships are beached,” she says.

Image courtesy of

Short on time: can EU shipyards get up to scratch?

Counterintuitively however, Jenssen believes shipowners kicking up a fuss over the new regulation can be seen as evidence of its necessity.

“There is comfort in the shipowners’ alarmist and distorted predictions, as it is a sign that the EU regulation will have its desired effect,” she says.

“Indeed, shipowners will be measured up against their use of the EU list, also for the vessels that do not sail under an EU flag. This risks hitting the poorly performing companies badly as shipping banks and investors are increasingly demanding higher standards and rightfully looking towards the EU for guidance.”

But Sand remains unconvinced. Shipowners, he says, are more than justified in their reaction to the latest developments.

“I don’t see any shipowners overreacting, but they are simply responding to avoid sub-par legislation that limits their ability to work freely in a truly global market,” he says.

“Some shipowners are actively working with the shipbreaking yards to improve facilities, but it’s a job that takes a long time.”

China's focus on the Hambantota Port is part of its ongoing strategy to build strategic footholds in South Asia