Company Insight

Treating Ballast Water at sea with EnviroCleanse

Sometime prior to the summer of 1988, a ship returning from Western Europe, bound for North America is full of ballast water and poised to pick up cargo somewhere in the Great Lakes. Unbeknownst to the crew, the ship is indeed laden with cargo, but not the kind you might expect. Buried deep in the bowels of the very water intended to keep the ship safe lurked a stowaway of sorts willing and able to wreak havoc on the fresh water lakes and canals of North America.

SPC Cone Fender System | Ferry Terminal | Sweden

Sometime prior to the summer of 1988, a ship returning from Western Europe, bound for North America is full of ballast water and poised to pick up cargo somewhere in the Great Lakes. Unbeknownst to the crew, the ship is indeed laden with cargo, but not the kind you might expect. Buried deep in the bowels of the very water intended to keep the ship safe lurked a stowaway of sorts willing and able to wreak havoc on the fresh water lakes and canals of North America.

No one knows for sure how or when Zebra Mussels arrived in North America, but on a hot summer day in 1988, a biologist and recent graduate research assistant found something that looked like a small stone. In one research expedition, the biologist was collecting water samples from a part of the Great Lakes’ water system that was known for its diverse biology. In this section of Lake St. Clair, water flows from Lake Huron to Lake Erie via the St. Clair River. While it cannot be known exactly when and where the first Zebra Mussel made its way into the Great Lakes, it is quite possible this ship from Western Europe released some of its ballast water unknowingly starting one of the greatest and most damaging ecological invasions we have ever witnessed. It didn’t take long for the Zebra and lesser known Quagga mussels to take hold of their new habitat. With no real predator, the organisms were free to move about and flourish in this newly-acquired and nutrient-rich environment. It was only a matter of time before biologists would discover what would ultimately spark one of the greatest environmental and regulatory reforms that the maritime industry had ever seen. It was not until almost 20 years later did we see regulations begin to emerge internationally that would address the issue.

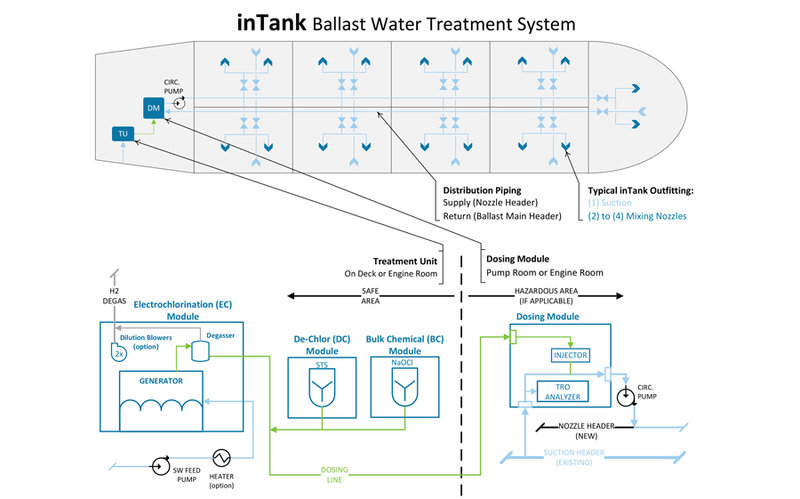

Fast forward another 20 years or so and we now have over 60 approved ballast water treatment systems by the IMO and, as of this article, nine approved by the US Coast Guard. While each system on the market varies in technology and treatment process, they all have one commonality that connects them – they treat during ballast operations. In a typical “in-line” treatment system, water is treated with an active substance or ultraviolet light. In either case, and to be effective, the water must pass through large filters which attempt to remove organisms and organic material larger than 40-50 microns. The thought is that by removing the larger of species, the disinfectant or UV concentration can be minimized and yield an effective treatment process. While this seems to work scientifically, it produces a harmful result to ship operations. As most ship operators know, ballast pumps were designed very specifically for a ship when it was constructed. When the ship was designed, much effort was put into sizing the ballast pumps for specific flow and pressure requirements to be able to effectively match the rates at which cargo is loaded and unloaded. When adding restriction to this process, ballast pumps are forced to be “de-rated” or even changed out as they are not capable of handling the newly installed treatment system. If that wasn’t enough, ship operators with in-line treatment systems are being forced to upgrade electrical systems to account for the tremendous load placed on existing generators by these new pieces of equipment, further complicating the issue. Finally, what happens if the system fails during port operations? The complications go on and on.

Caption

Enter Envirocleanse… When investigating a better method to treat ballast water, it became abundantly clear that treating at port was NOT the preferred method. There was little power available for a new system. There was not enough margin available for slowing down loading and unloading of cargo. And, there was simply too much risk if the system were to become inoperable. With the Envirocleanse inTank BWTS, we have addressed those concerns. The inTank system performs the treatment process in a very simple manner – by circulating the ballast water and injecting disinfectant during the voyage. By treating at sea, the ship has much more power available for a new treatment system. Shipboard cranes are idle, ballast pumps are not running and generally the ship’s power load is low. More importantly, the inTank BWTS does not require filters. By using time and a prescribed concentration of sodium hypochlorite, the system can treat the ballast water to compliant levels without having to use costly and large filtration units. Finally, by treating at sea, the crew has valuable time should any issues arise with equipment or the treatment process. This enables the ship to continue operations and avoid costly upsets at port which could result in having to leave and return.

While it is commonly agreed-upon that there is no method for ballast water treating that will be the perfect solution for every vessel, the inTank BWTS certainly has advantages for the ship owner that are indisputable. By taking away risk to port operations, ships can continue to operate “normally” with no additional duties or requirements inherent to systems treating during uptake and discharge.

POOR PLANNING AND OVERCONFIDENCE: THE MAIB’S MAIN FINDINGS

If there is one takeaway point from the inquiry it is that poor planning was at play.

Investigators discovered the lead pilot had not informed the bridge team of his plan for the turn around Bramble Bank. There was an “absence of a shared understanding of the pilot’s intentions for passing other vessels or for making the critical turns during the passage”.

Elsewhere, the master and port pilots were blamed for “complacency and a degree of over-confidence”.

There was an “absence of a shared understanding of the pilot’s intentions”

CMA CGM, which took delivery of the Vasco de Gama in July 2015, has acknowledged MAIB’s findings, and claims to be addressing the aforementioned issues raised in the report.

“Following this grounding, CMA CGM and ABP [Associated British Ports] Southampton have been working together,” said a spokesperson for the company in an email.

“As mentioned in the MAIB official report, CMA CGM has already taken measures to prevent this type of incident to happen again. CMA CGM is strongly committed to ensuring the safety of its operations and its crews in accordance with local and international regulations.”

All straight-bat stuff. ABP could not be reached for comment.

Unavoidable inquiry: why the MAIB inquiry needed to happen

Simon Boxall, a maritime expert from the University of Southampton, believes MAIB’s findings to be fair, despite Bramble Bank’s reputation as “a navigation hazard” due to it susceptibility to “slight movement after major storms”.

“Looking through the report there was no evidence of unforeseen mechanical failure on the ship, nor of abnormal weather conditions,” he says.

“On that basis, the two pilots and the ship’s master should have been in a position to safely navigate the vessel into port. It would appear to be user error – which is what the report says in so many words.

Introducing ways of reducing user error can only be seen as a good move

“In light of this, introducing ways of reducing user error can only be seen as a good move.”

Boxall also acknowledges things could have been a lot worse. As the Vasco de Gama was re-floated relatively quickly, the port didn’t suffer any kind of blockage – which, given the vessel’s size, would have brought Southampton to “a standstill”.

Neither did the vessel endure any serious damage. Nonetheless, an investigation was still necessary.

“If reports such as this are not produced then the safe navigation of shipping is not improved,” says Boxall.

“In the same way an airline near-miss is thoroughly investigated, it is important that the same is done for shipping – not as a witch hunt, but as a fact finding investigation to improve safety.”

Svein Kleven is senior vice president of engineering and technology for Rolls-Royce. Image courtesy of Rolls-Royce